Lecture 23 - Evaluating ML models: Metrics for Regression and Classification¶

Announcements¶

- Reminder: Lab 7 is due Sunday 11/30; no late penalty applied before 10pm Wednesday 12/3; no submissions accepted after that (not even via slip days)

Goals¶

- Know how to think about errors regression problems, and a few ways they can be measured.

- Regression: absolute, relative, squared; MSE, RMSE, MAE, coefficient of determination

- Binary Classification: accuracy, precision, recall, F-score

- Multiclass classification: acccuracy, precision, recall,

So you've made some predictions. How good are they?¶

Regression Metrics¶

Let's consider regression first. Our model is some function that maps an input datapoint to a numerical value:

$y_i^\mathrm{pred} = f(x_i)$

and we have a ground-truth value $y_i^\mathrm{true} $for $x_i$.

How do we measure how wrong we are?

Error is pretty simple to define:

$y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}$

But we want to evaluate our model on the whole train or val set. Average error is a bad idea:

$\sum_i y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}$

Absolute error solves this problem:

$|y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}|$

Mean absolute error measures performance on a whole train or val set:

$\frac{1}{n} \sum_i |y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}$|

Squared error disproportionately punishes larger errors. This may be desirable or not.

$\sum_i \left(y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}\right)^2$

Mean squared error (MSE) does the same over a collection of training exaples:

$\frac{1}{n} \sum_i \left(y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}\right)^2$

MSE becomes more interpretable if you square-root it, because now it's in the units of the input. This gives us Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

$\sqrt{ \frac{1}{n} \sum_i \left(y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}\right)^2}$

Problem with any of the above:

You can make your error metric go as small as you want! Just scale the data: $$ X \leftarrow X / k $$ $$ \mathbf{y}^\mathrm{true} \leftarrow \mathbf{y}^\mathrm{true} / k $$ $$ \mathbf{y}^\mathrm{pred} \leftarrow \mathbf{y}^\mathrm{pred} / k $$

Also: Is 10 vs 12 is a bigger error than 1 vs 2?

Solutions:

Relative error:

$|y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}|$

Coefficient of determination:

Let $\bar{y}$ be the mean of $\mathbf{y}^\mathrm{true}$.

Let $SS_\mathrm{tot} = \sum_i \left(y_i^\mathrm{true} - \bar{y}\right)$.

Let $SS_\mathrm{res} = \sum_i \left(y_i^\mathrm{true} - y_i^\mathrm{pred}\right)$.

Then the coefficient of determination is: $1 - \frac{SS_\mathrm{res}}{SS_\mathrm{tot}}$

This is:

- 0 if you predict the mean

- 1 if you're perfect

- negative if you do worse than the mean-prediction baseline!

Classification Metrics¶

Evaluating binary classification is trickier than regression, and the reason is that most intuitive metrics can be gamed using a well-chosen baseline.

Simplest metric - accuracy: on what % of the examples were you correct?

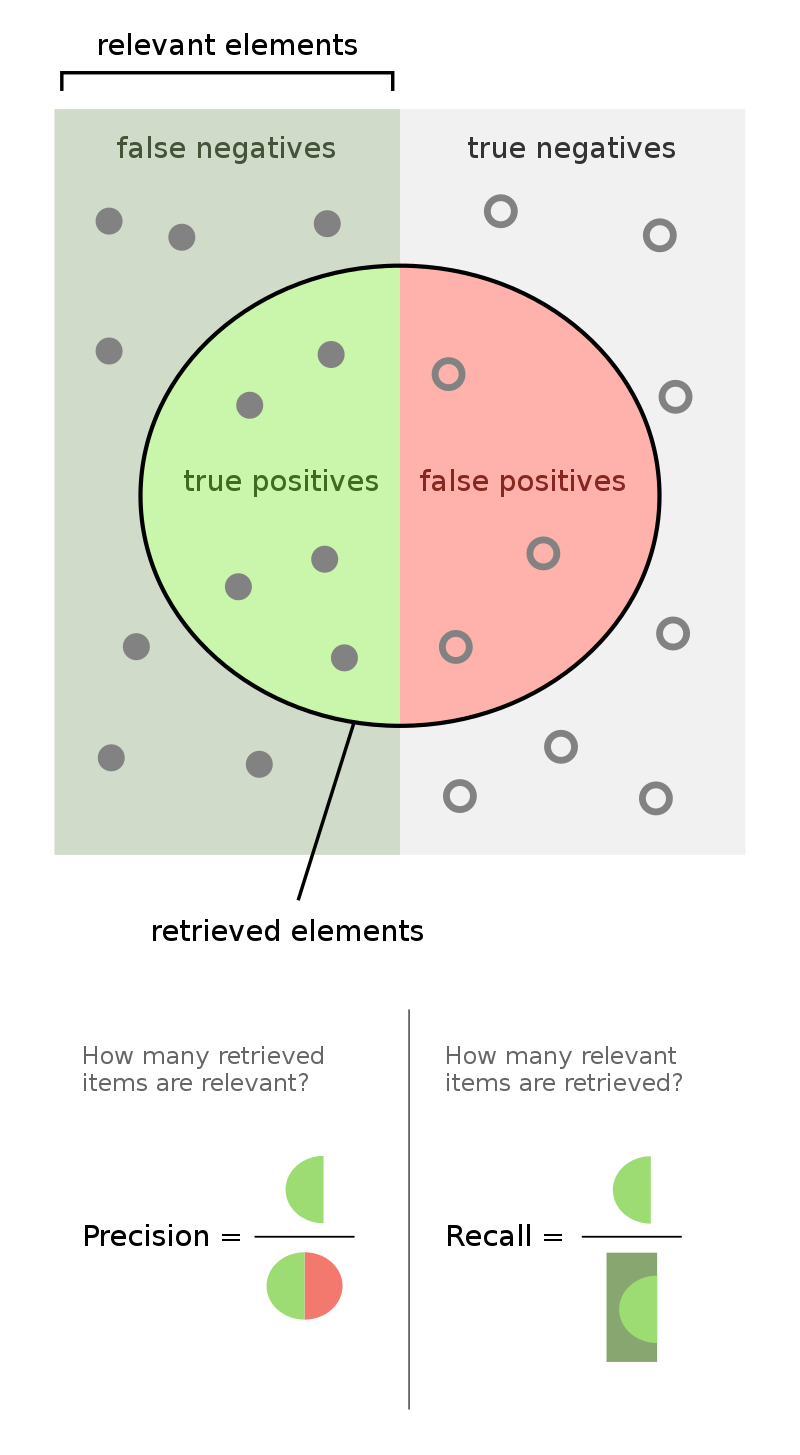

There are different kinds of right and wrong:

- TP - True positives (correctly labeled positive)

- TN - True negatives (correctly labeled negative)

- FP - False positives (incorrectly labeled positive; was actually negative)

- FN - False negatives (incorrectly labeled negative; was actually positive)

Exercise: let TP be the number of true positives, and so on for the other three. Define accuracy in terms of these quantities.

Accuracy = $\frac{TP + TN}{(TP + TN + FP + FN)}$

Exercise: Game this metric. Hint: suppose the classes are unbalanced (95% no-tumor, 5% tumor).

Problem: if you just say no cancer all the time, you get 95% accuracy.

Okay, what's really important is how often you're right when you say it's positive:

Precision = $\frac{TP}{(TP + FP)}$

Anything wrong with this?

Problem: incentivizes only saying "yes" when very sure (or never).

Okay, what's really important is the fraction of all real cancer cases that you correctly identify.

Recall = $\frac{TP}{(TP + FN)}$

Exercise: Game this metric.

Problem: you get perfect recall if you say everyone has cancer.

Can't we just have one number? Sort of. Here's one that's hard to game:

F-score $= 2 *\frac{\textrm{precision } * \textrm{ recall}}{\textrm{precision } + \textrm{ recall}}$

Here's a visual summary (source: Wikipedia):

Tuning a Binary Classifier¶

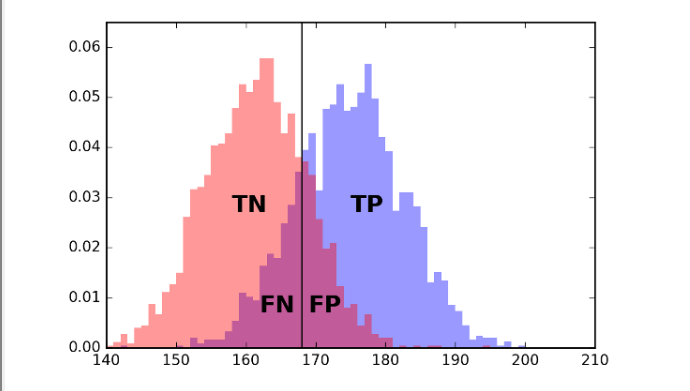

Sometimes your classifier will have a built-in threshold that you can tune. The simplest example is a simple threshold classifier that says "positive" if a single input feature exceeds some value, and negative otherwise.

Consider trying to predict sex (Male or Female) given height:

If you move the line left or right, you can trade off between error types (FP and FN).

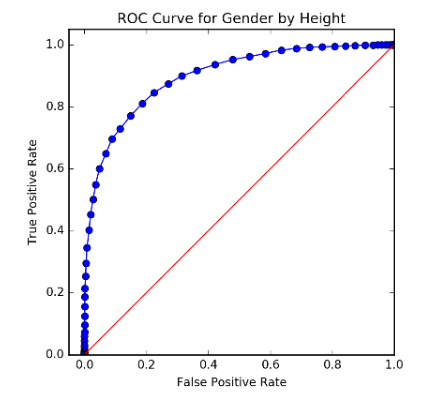

The possibilities in this space of trade-offs can be summarized by plotting FP vs TP:

Multi-Class Classification¶

Usually, a multiclass classifier will output a score or probability for each class; the prediction will then be the one with the highest score or probability.

Metrics:¶

- Accuracy - still possible, but random guess baseline gets worse fast, and good accuracy is very hard to get with many classes.

- Top-k accuracy: does the correct class lie in the $k$ most likely classes? Easier, and gives "partial credit"

- Precision and recall can be defined for each class:

- Precision for class $c$: $\frac{\textrm{\# correctly labeled } c}{\textrm{\# labeled class } c}$

- Recall for class $c$: $\frac{\textrm{\# correctly labeled } c}{\textrm{\# with true label } c}$

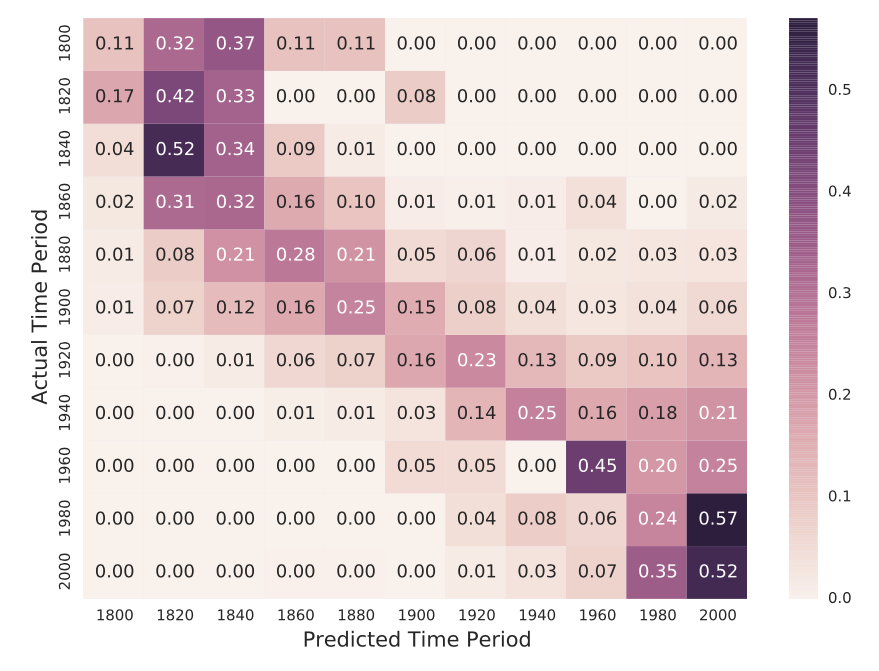

The full performance details can be represented using a confusion matrix:

Exercises: Given a confusion matrix, how would you calculate:

- the precision for a certain class?

- the recall for a certain class?